[our friend and colleague, Dr Clare Taylor, from Open University, is our guest blogger again for this blogpost – thank you again Clare for taking the time to share your research – you can also read Clare’s other blogpost from 19th Feb 2021, HERE].

Mark

Here’s Clare Taylor’s blogpost:

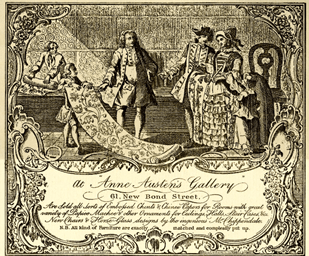

‘Many of the names behind leading antique dealers were men, but women’s role in the business equally deserves to be uncovered and celebrated, as Mark’s 2015 posts on the early B.A.D.A. member Clara Millard revealed [HERE & HERE]. Women, too, have a long association with the trade [Mark – indeed they do, the dealer Jane Clarke (c.1794-1859), who specialised in ‘antique lace’, was a major dealer in the middle decades of the 19th century – see also my dictionary of 19th century antique dealers – White Rose Depository ] and at least one female dealer looked back to the eighteenth-century to advertise her shop. Anne Austen adapted the c.1754 trade card of James Wheeley, a paper hanging warehouseman on Aldersgate Street, for her own business on New Bond Street, which was visited by Prince Henry of Battenberg in 1912 [Mark – see Anne Austin in the Antique Dealer Project Map website too – HERE ]. Austen kept Wheeley’s cartouche and shop scene but changed the name and address. She also adapted the wording, removing the wallpaper manufacturing element from Wheeley’s card and substituting ‘common papers’ with the presumable more valuable ‘Chinee papers’ or Chinese wallpapers, adding ‘New Chairs & Horse Glass designs by the ingenious Mr. Chippendale’ to the list of items she sold.

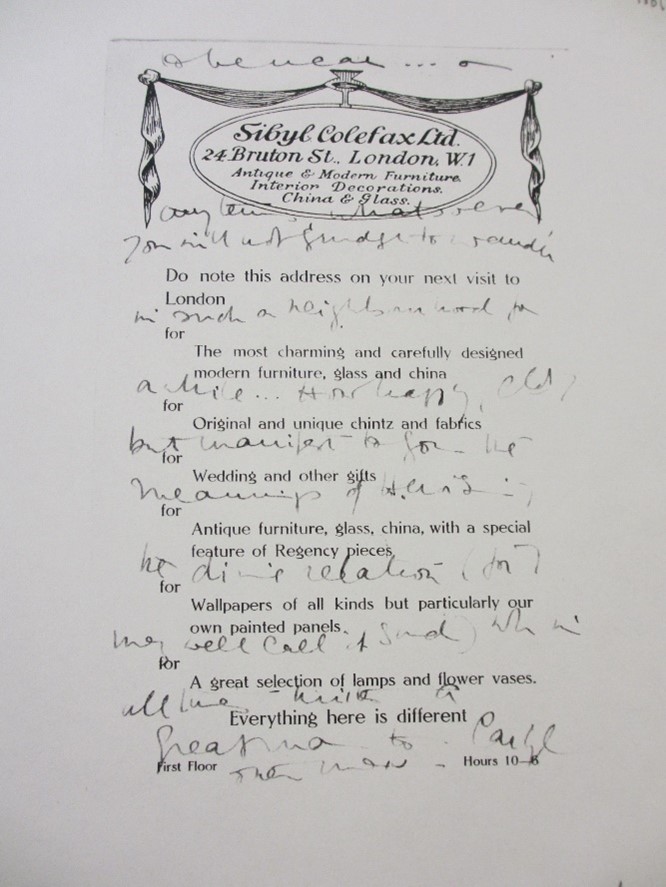

Austen’s card suggests she was fitting up interiors, and decorating was frequently thought of as the preserve of amateurs who gave ‘advice’, but became nevertheless an important area for women seeking work (and an income) in the early years of the twentieth century and often went hand in hand with the trade in antiques. Sybil Colefax (1875-1951) was in just such a position in the 1920s. These women trod a difficult path, as Virginia Woolf’s description of Sybil in a letter of 1930 to Vanessa Bell conveys, since in Woolf’s view Sybil ‘is now of the family of Champcommunal and other money makers’, ‘a hardened shopkeeper’, whose society life of leisure has been replaced by a working life such as that of Elspeth Champcommunal (1888-1976), the then Editor of Vogue magazine.

Sybil’s name is now synonymous with the decorators Colefax & Fowler, and although her role in that firm might have been short lived (1938-46) and her contribution since eclipsed by those of John Fowler and Nancy Lancaster, Sybil’s knowledge of antiques was built up over a much longer timeframe. She had started out before the Second World War working for Stair & Andrew, establishing their decorating department on the first floor at Bruton Street, so her early knowledge may well have been gleaned from working with their stock, although according to her biographer later ‘forays into Bond Street…brought her into contact with many London dealers’. Her trade card certainly highlighted that she supplied ‘Antique furniture, glass, china with a special feature of Regency pieces’ and it was a lighter version of Edward Knoblock’s Regency taste which she promoted with painted and gilded chairs, console tables and textiles in plain satin or printed with Regency-style motifs such as bay leaf circlets and lyres.

Her own manuscript, ‘On Houses’, also signified the importance of the setting in which antiques were placed, warning that ‘ You lose half the effect of a fine Queen Anne writing table or bookcase or walnut chairs…when they’re set among some dull creton [sic] or linen covers of poor design and washy colour’. It also seems that clients recognised her expertise in antiques as well as interiors. During the War she kept her business going whilst helping out at the Red Cross depot and in May 1940, a desperate Marquess of Anglesey, for whose wife, Marjorie Manners, Sybil had decorated a bedroom at Plas Newyyd, wrote that he had no money and no jewels (‘except as will belong to the children, as they want them’) to send to the Red Cross sale. He sought Sybil’s advice to authenticate a piece of furniture, asking, ‘What about the Empire piece. Do you think it has a History? Or can you say with authority that it comes from Malmaison? Can you advise me whether it could be written over as famous and historical and sent to the Lord Mayor?’

A key element of the Regency Revival taste for which Sybil Colefax was admired was decorated and painted furniture, a taste which is still with us today. From the early 1920s such pieces were sold by the decorator Syrie Maugham (1879-1955) from her shop on Baker Street, who had a reputation for ‘pickling’, bleaching and painting in white pieces from eighteenth-century commodes to mirror frames.

Liberty’s, Heal’s and Peter Jones on Sloane Square also sold painted pieces, supplied in the case of Peter Jones not only by Maugham but by the artists Ambrose Thomas (‘The Marquis d’Oisy’) and Margaret Kunzer. By 1930 Kunzer had been recruited to head a Department of Decorative Furniture for the shop, and during the early 1930s a painting studio was established in nearby Ixworth Place to feed in stock, run by a young John Fowler. Stock sold out at the first exhibition held in the Department and demand continued to grow. One determinant was clearly price. Kunzer went on buying trips and had a regular supplier in Suffolk who repaired pieces ready for painting (a Mr Head in Sudbury) but she also bought pieces closer to home once paying £10 in the Caledonian market (also a source of pieces for Syrie Maugham) for ‘a small pine tallboy, a writing table, several chairs and a tray’ which all needed only minor repairs before being painted. However, Kunzer also had a keen eye for what would sell, recalling in 1982 that at an exhibition held early in 1935 it was Regency pieces that were most in demand as they were suited to customers who were increasingly living in smaller scale flats and houses.

These examples, of Anne Austen, Sybil Colefax, Syrie Maugham and Margaret Kunzer, illustrate some of the different ways in which women contributed to the trade in antiques in the interwar years and after, and offer tantalising glimpses of the networks within which these women operated and their role in promoting new tastes.

Clare Taylor.

Leave a comment