We were fortunate to acquire a small cache of old auction catalogues at auction last week (thank to Keys Auctioneers in Norfolk for the careful packing and posting!). I normally look out for old auction catalogues anyway as they are increasingly rare (especially small local auction sales of country house contents), but this set of catalogues has proved to be especially interesting as they had previously belonged to members of the well-known Levine family of antique dealers based in Norfolk. They give us a fascinating insight into early-and-mid 20th century antique dealing.

The Levine family started as antique dealers in Norfolk in the 1860s with shops in Norwich and Cromer. Levine became specialists in antique silver, becoming a member of the British Antique Dealer’s Association (BADA) in 1920. Louis Levine (1865-1946) established Louis Levine & Son in the late 19th century and had shops in Prince of Wales Road, Norwich in 1900 – he was described as ‘Dealer in Plate, Jewels and etc.’ and as ‘Dealer in Antiquities’ in the 1901 and 1911 Census; he also had a shop in Church Street, Cromer and a shop in London (192 Finchley Road) from the mid 1920s. Rueben Levine (1865-1927), the son of a jeweller Moses Levine, was another member of the Levine family of antique dealers, establishing his business in 1891. Another family member, Edward David Levine (1906-1984) established an antique dealing business in 1931, employing his brothers Victor Jacob Levine (1896-1934) and Henry Levine (1904-1978); Henry established his own antique dealing business in 1935. It’s not unusual for a family to generate multiple antique dealing businesses – see our ‘guest’ blogpost in May 2025 by Andy King on the Lock family of dealers.

The auction catalogues range in date from the 1870s to the 1940s and relate to some significant country house auctions in Norfolk, Suffolk and the surrounding area, including Playford Hall, Ipswich (contents sold by Garrod, Turner & Son in March 1936); Finborough Hall, Suffolk (contents sold by H.C. Wolton in October 1935); Hengrave Hall, Suffolk (contents sold by Salter, Simpson & Sons in March 1946), Carelton Hall, Saxmundham, Suffolk (contents sold by John D. Wood in June 1937) and which was destroyed by fire in 1941, and Thornham Hall, Eye, Suffolk (contents sold by Garrod, Turner & Son in May 1937), which was partially demolished following the auction of the contents and finally destroyed in a fire in 1954.

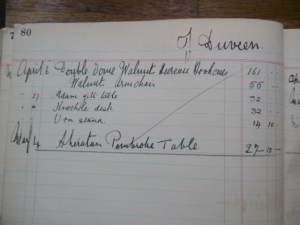

These 1930s and 1940s auction catalogues seem to relate to the Levine antique dealing business at 74a Prince of Wales Road, Norwich run by ‘R. Levine’, (Rueben Levine) established in 1891. A signature in an auctioneers slip that still remains in the Thornham Hall catalogue is that of ‘G. J. Levine’ (not quite sure who this is in the Levine family?) and an address 74a Prince of Wales Road, Norwich.

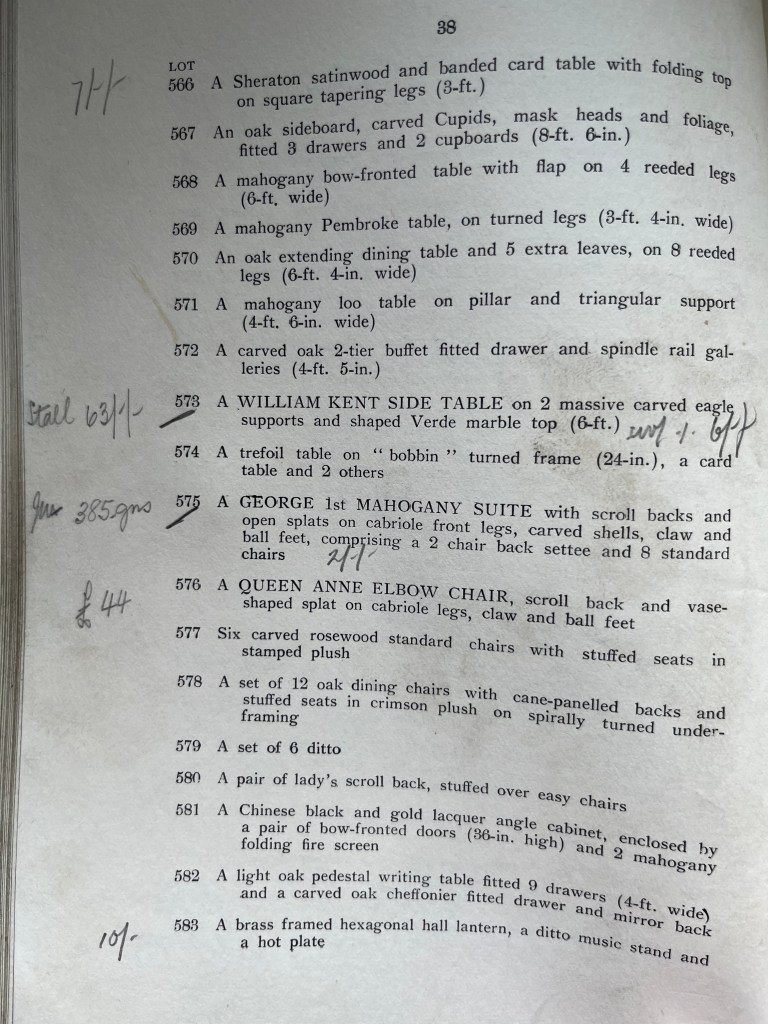

The Thornham Hall catalogue also contains annotations made by Levine, indicating maximum bids and some prices realised (in pounds, shillings and pence) with the names of other antique dealers who had bought important lots. Below (see picture), Lot 573, ‘A WILLIAM KENT SIDE TABLE’ was bought for £63 by the London dealer Isaac Staal & Sons (Levine writes it as ‘Stall’) important dealers in antique furniture with a smart shop in Brompton Road, London at the time. Lot 575, ‘A GEORGE 1ST MAHOGANY SUITE’ made the enormous sum of 385 guineas (£404 and 5 shillings – equivalent to about £148,000 at the time). Unfortunately there are no illustrations of the Lots in the catalogue.

Levine tends to write out dealer names in full next to the Lot numbers and there are some familiar dealers listed as buyers – Rixon, Lee, Mannheim, Cohen etc. The buyer of Lot 575 is noted as ‘JW’, listed by Levine as the buyer of many Lots at the Thornham Hall auction. ‘JW’ is obviously someone familiar to Levine and is almost certainly the dealer John Wordingham. Wordingham established his antique dealing business in 1908 and was a member of the BADA. He had been a neighbour of Levine at 74 Prince of Wales Road in the 1920s, but by the 1930s (at the time of the auction) he was trading from the famous 16th century ‘Augustine Stewards House’, Tombland, Norwich. Below is a photograph of Wordingham’s shop in 1935 just a couple of years before the Thornham Hall auction.

The auction catalogue of ‘The Shubbery, Hasketon, Woodbridge, Suffolk’ (contents sold by Arnott & Everett in April 1939) clearly illustrates the specialist interest of the Levine family as antique silver dealers. In the sections of antique silver in the catalogue (see below) there are lots of annotations and prices with names of various well-known London-based antique silver dealers as buyers – ‘Kaye’ (Angel & Kaye, silver dealers established in the 1930s); ‘Black’ (David Black, silver dealer established in 1915).

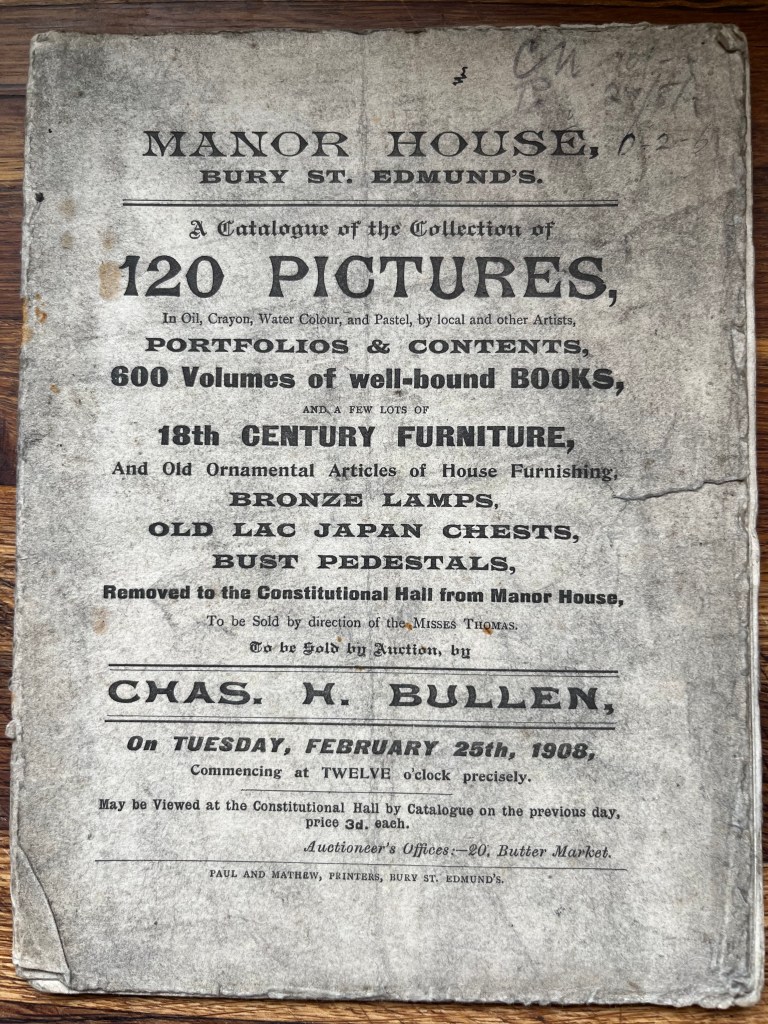

As well as the catalogues from the 1930s and 1940s, six of the catalogues date from 1908 and have various annotations signed by ‘R. Levine’ so maybe by Rueben Levine (1865-1927) himself? The catalogue of the contents of ‘Manor House, Bury St. Edmunds’ (sold by Charles Bullen in February 1908) is particularly interesting.

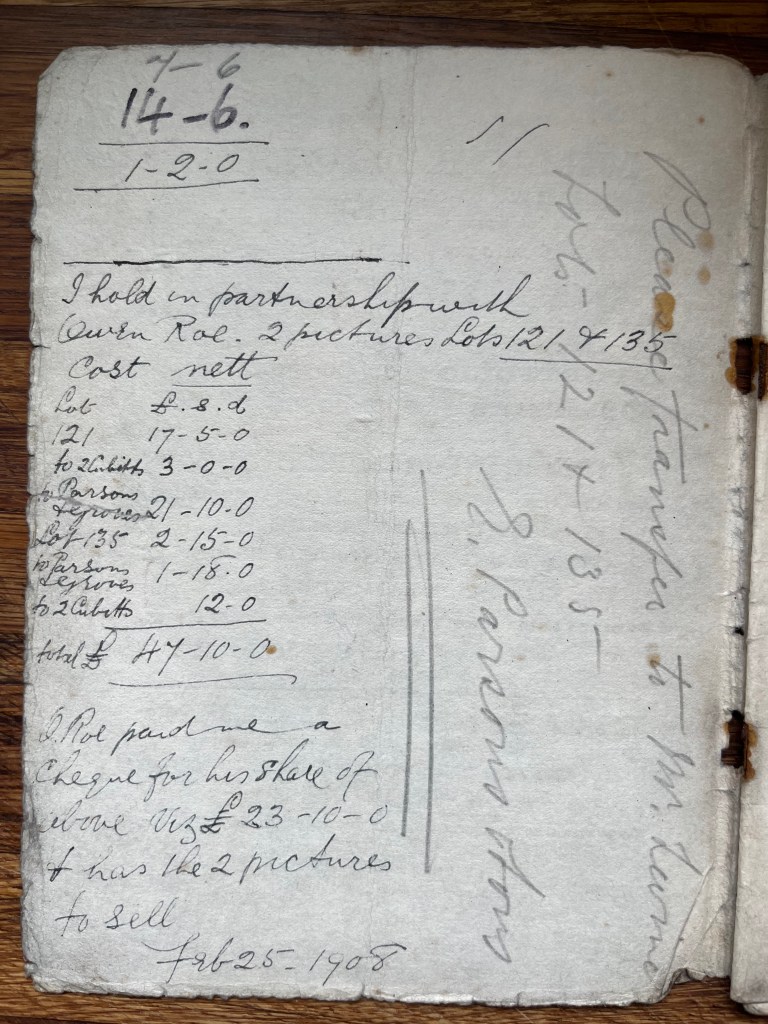

The Manor House catalogue has two intriguing hand written notes on the verso of the front cover (see below). The notes relate to 2 paintings sold at the auction. The note written in pen (to the left in the photograph) states ‘I hold in partnership with Owen Roe. 2 pictures Lots 121 & 135’, which cost a ‘total of £47-10-0’. It also has a note at the bottom stating ‘O. Roe paid me a Cheque for his share of above Viz £23-10-0 & has the 2 pictures to Sell. Feb 25-1908’. Owen Roe was an antique dealer trading from various shops in Cambridge, the business began in the late 19th century and continued in the family until the mid 1970s.

What is really interesting about the note is the list of sums of money to the left, which state: ‘Lot 121’ ‘£17-5-0’, and then below, ‘to 2 Cubitts £3-0-0’; ‘to Parsons & Sons £21-0-0’; then ‘Lot 135’ ‘£2-15-0’, and then below, ‘to Parsons & Sons £1-18-0’; ‘to 2 Cubitts 12-0’; ‘total £47-10-0’ – (I seem to make it £46-10-0, but maths is not my best subject!). Now this all looks somewhat opaque until one notices the other handwritten note in pencil (at 90 degrees) to the right. Here it states ‘Please transfer to Mr Levine lots 121 & 135, E. Parsons & sons’.

What these handwritten notes seem to point towards is an auction ‘ring’. ‘Please transfer to Mr Levine’ indicates that ‘E. Parsons’ was the buyer of the paintings at the auction but for some reason transferred his purchases to Levine. This is classic ‘ring’ activity – indeed one of the key aspects of attempts to stop the ‘ring’ is that auctioneers now specifically disallow transfers between buyers.

For those that are not aware – the ‘ring’ is where dealers would agree amongst each other not to bid against one another at an auction; one dealer was designated by the other dealers to bid for the Lot or Lots at the auction. The dealers would then re-auction any Lots bought in the ‘ring’ in a private auction (known as the ‘knockout’) after the auction (often in the local pub or other venue). The resulting price difference between the object sold at the public auction and the price eventually realised at the private auction was distributed amongst the participants of the ‘ring’. The practice was legal throughout the 19th century, although it was highly criticized. Indeed, it was not until the 1920s that the legitimacy of the practice became more formally and legally questioned, and not until 1927 that the practice was made a criminal offence (The Auctions (Bidding Agreements) Act 1927). So in 1908, when Levine, Roe, Parsons and Cubitt bought/sold the 2 paintings at the Manor House auction, the practice was frowned upon, but not yet illegal.

You can read a little more about the auction ring in the exhibition catalogue ‘SOLD! The Great British Antiques Story’ (exhibition at The Bowes Museum in 2019) – the catalogue for the exhibition is freely available online via White Rose Depository.

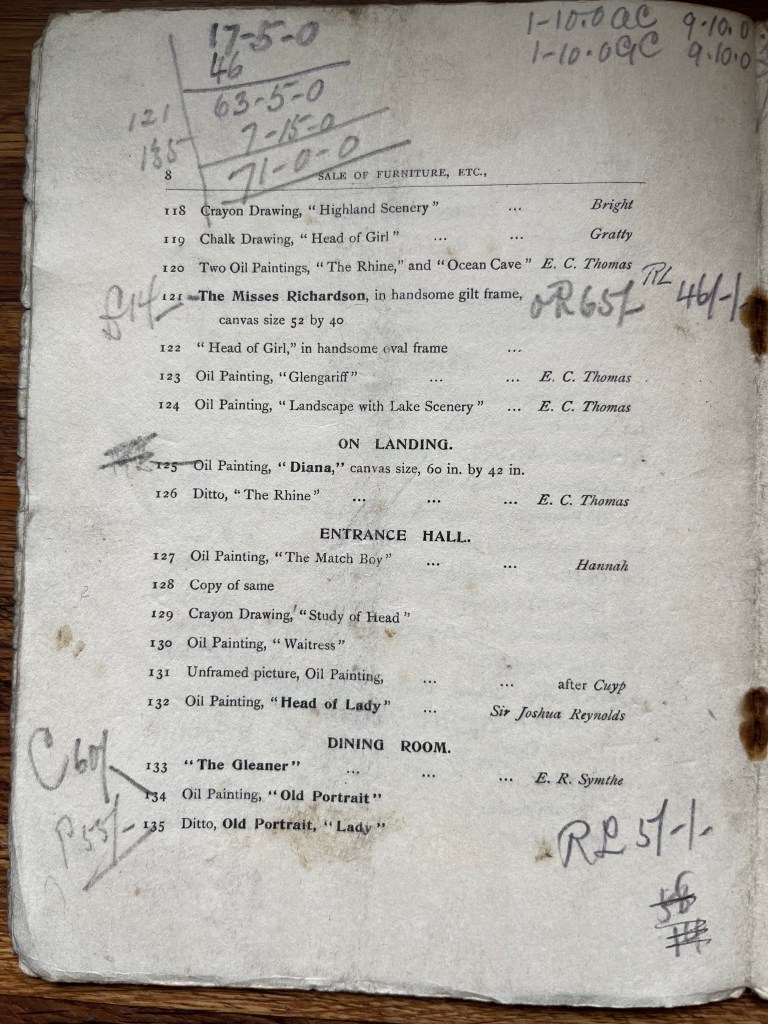

There is further evidence of the operation of an auction ‘ring’ at the 1908 Manor House sale when one looks at the catalogue entries for Lot 121 and Lot 135 (see below). There are a number of annotations associated with the Lots – Lot 121, for example, has a note stating ‘£14’, but also has ‘OR’ (Owen Roe) ’65/-‘ (65 shillings, which was £3-5-0); and ‘RL’ (Rueben Levine) ’46/-‘ (46 shillings, which was £2-6-0). For Lot 135, there are similar annotations – ‘C60/-‘ (which I guess refers to Cubitt and 60 shillings, which was £3); ‘P55/-‘ (which I guess refers to Parsons and 55 shillings, which was £2-15 shillings), and ‘RL 5/-/-‘ (which I guess refers to Reuben Levine and 5 pounds). Above this in the top left is another list of sums of money ‘£17-5-0’ with ‘£46’ beneath it, and then [lot]121 ‘£63-5-0’ and [lot]135 ‘£7.15-0’, with a sum total of ‘£71-0-0’. These notes seem to indicate bids or commitments by Parsons, Cubitt, Roe and Levine for the 2 paintings.

But who were Parsons & Sons and Cubitt? Parsons & Sons were antique dealers who by the 1920s were trading in the then ultra-fashionable Brompton Road, London. Cubitt & Sons were also well-known antique dealers, trading in Norwich and London – in fact at the time of the auction sale in 1908 they occupied the building next door to what would become John Wordingham’s shop in Tombland in Norwich, the famous ‘Hercules House’ (see the building below – you can just see what would become Wordingham’s shop in the 1930s to the left). George Cubitt also operated as an auctioneer in the same period, also trading from Hercules House (also known as ‘Hercules and Samson House’); in fact George Cubitt took the famous auction at Walsingham Abbey, Norfolk in September 1916.

So, this little cache of country house auction catalogues contain fascinating insights into the workings of the antique trade in the early-to-mid 20th century and are a really significant acquisition for the antique dealer archives and ephemera we are assembling at the University of Leeds. They will, of course, be joining the other dealer material at the Brotherton Library Special Collections at the University of Leeds in due course.

Mark