A couple of months ago my friend and colleague Diana Davis very kindly sent me a link to a short black & white film of the 1932 Art Treasures Exhibition (thank you Diana!), and which obviously pricked my interest as it is full of objects that were being sold by antique dealers. You can watch the film in YouTube (it’s only 2 minutes 49 seconds long) HERE – the original film is part of the wide range of historic films and TV archives held by British Pathe (link HERE).

The Art Treasures Exhibition, held at Christie’s auction rooms, King Street, London, 12th October to 5th November 1932 and organised by The British Antique Dealer’s Association (BADA) is fairly well-known amongst historians and those interested in the history of the art market. The 1932 exhibition followed on the success of the earlier BADA organised exhibition at Grafton Galleries, London in 1928. Both exhibitions prefigured the establishment of the Grosvenor House Antiques Fair (also known as ‘The Antique Dealers’ Fair’) which began in 1934 – (see also some older blog posts on The Grosvenor House Fair etc in January 31st 2021 and April 23rd 2015).

Fortunately, we have a copy of the 1932 Exhibition catalogue, so it’s possible to match up some of the objects in the film to those in the catalogue and find out which dealers are behind the objects, so I thought it would be an interesting exercise to do that!

The film of the 1932 Exhibition is a fascinating period piece from the early 1930s, obviously created as a publicity newsreel for the exhibition. The narrator (unknown), guides the viewer to some of the highlights of the exhibition at the time, telling the background stories of some of the objects offered for sale by various antique dealers, but also offering a visual insight into the displays at the exhibition. Below, for example, is a screenshot of a general panning shot (do watch the YouTube film for effect) of one of the stands which appears to have a mixture of dealers’ objects – the large pair of urns are certainly item No.237 in the catalogue, ‘A pair of satinwood knife boxes, c.1790, originally made for Lord Northesk’ (the family seat is Ethie Castle, near Arbroath) and offered by the antique dealer Rice & Christy, Wigmore Street, London; the tapestry behind looks like it is No.285 ‘A Beauvais Tapestry, c.1790’, offered by The Spanish Art Gallery, Conduit Street, London; and the display cabinet to the left is certainly No.182 ‘A Chippendale China Cabinet, c.1765′ offered by M. Harris & Sons. So I guess this panning shot was of a collection of various dealers’ objects at the entrance to the exhibition, indicating the sheer range of things offered for sale?

The Exhibition had 1,380 objects, and the film obviously does not cover all of them, but there are 13 objects highlighted in the film, so for those that watch the film, here’s some information on the dealers who were behind the objects (and a little bit of information on where the objects are now, if it has been possible to trace them) – I’ll do this in the sequence of the objects highlighted in the film by the narrator:

1st object – (see below) in the film the narrator spends a few moments on this object; it is also object No.1 in the catalogue: ‘An embroidered Throne used Queen Elizabeth, English 1578’; this was offered by the well-known London antique dealers Acton Surgey Ltd & Mallett & Son. Thanks to our friends William DeGregorio and Chris Jussel (in the USA) we know that the embroidered throne made its way into the collection of Sir William Burrell (1861-1958) and remains in the Burrell Collection in Glasgow (it is currently in storage at The Burrell – see below).

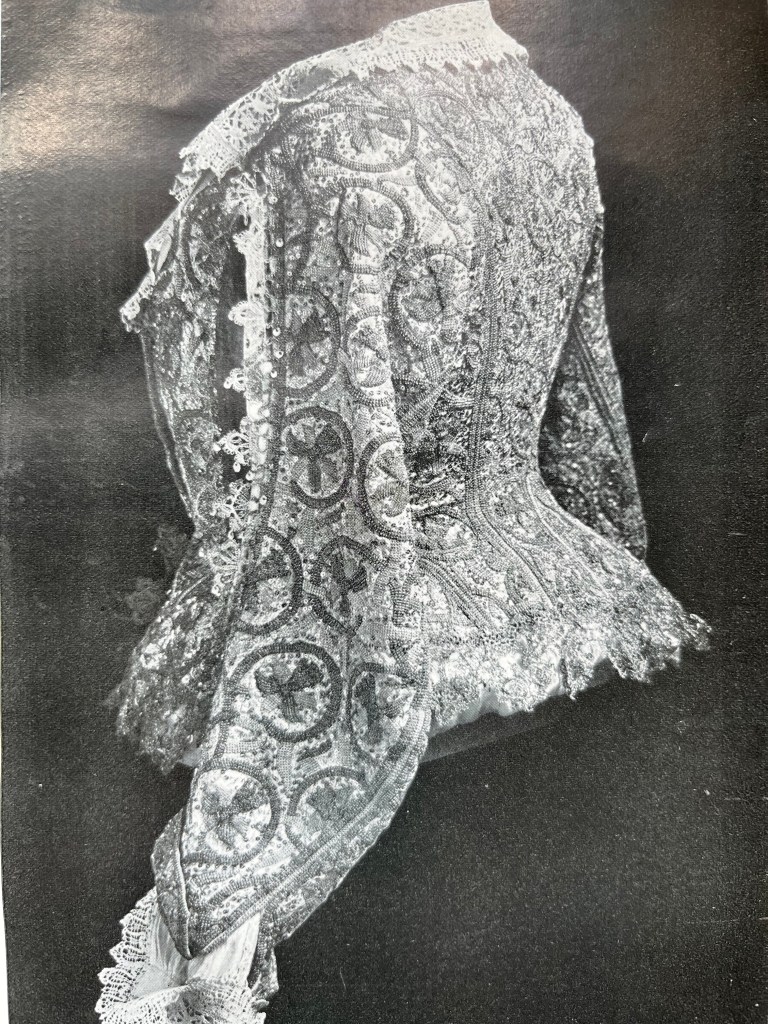

2nd object – (see below) mentioned by the narrator is No.2 in the exhibition catalogue, ‘A gold embroidered jacket, lace shirt, and gloves, English, late 16th century’; it was also offered by Acton Surgey Ltd; the jacket is now in the collections of Boston Museum of Fine Arts in the USA. It was purchased from Acton Surgey by the collector Elizabeth Day McCormick (1873-1957) in 1943 and gifted to the Boston MFA. It is not known what happened to the shirt or the gloves; and it has not also been possible to identify the ‘gold and enamelled jewel set with diamonds and rubies’ that the Narrator also mentions.

3rd object – (see below) the narrator describes a ‘Gothic tapestry, over 400 years old’, this is either No.270 or No.271 in the catalogue. Neither are illustrated in the catalogue, but are both described in the catalogue as ‘A panel of Gothic tapestry, Franco-Flemish, circa 1500’ and both are offered by The Spanish Art Gallery Ltd, Conduit Street, London. It has not been possible to trace the present whereabouts of the tapestry.

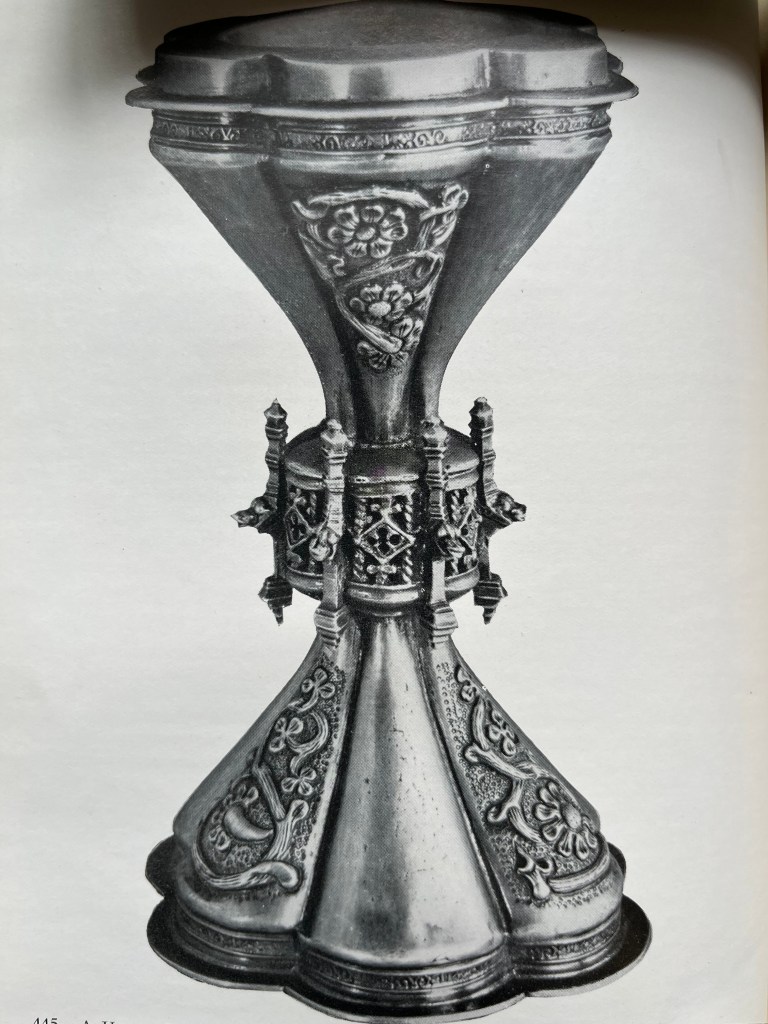

4th object – (see below) this is described by the narrator in the film as ‘a fine specimen of a Henry VII salt-cellar in hour-glass form’. This is No.445 in the catalogue; ‘A Henry VII silver-gilt standing salt, London 1505’. It is also illustrated in the catalogue, and was offered by the antique silver dealers Crichton Brothers, then trading at 22 Old Bond Street, London. It has not been possible to trace the Henry VII salt – the narrator in the film suggested that it was the only known piece of silver with the date 1505, so I guess if it does still exist, it must be easily identifiable? (our friend Chris Coles spotted the salt in a 1969 exhibition catalogue produced by The Goldsmiths Company….so perhaps the salt is in the collections of The Goldsmiths – thanks Chris!)

5th object – (see below) the narrator describes a ‘stand for a porringer or tankard….previously owned by the diarist Samuel Pepys’. This is No.618 in the catalogue – ‘The Charles II silver-gilt ‘Pepys’ tazza, London 1678′. It is not illustrated in the catalogue, but was also offered by the antique silver dealer Crichton Brothers. The ‘tazza’ is now in the collections of The Clark Institute in Massachusetts in the USA. It was commissioned by Samuel Pepys (1633-1703) in 1678 and was sold at Sotheby’s on 1st April 1931 (Lot 3) to Crichton Brothers, who appear to have sold it to the American silversmith and art curator Peter Guille of New York, who sold it to Robert Sterling Clark in 1946.

6th object – (see below) described by the narrator as a ‘Chippendale chair’, but I can’t find this chair (or even a set of them) listed in the exhibition catalogue; perhaps it was a late edition to the exhibition?

7th object – (see below) the narrator describes 3 walnut chairs, ‘made about 1690’. There are a number of such chairs in the exhibition catalogue, but without a photograph of them from the catalogue it has not been possible to identify which of the chairs the narrator is referring too? However, the centre chair, could be No.50 in the catalogue, ‘A William and Mary armchair of small size, circa 1690’, and said to have ‘traditionally been used by Queen Anne’; it was offered for sale by the well-known dealers Moss Harris & Sons.

8th object – (see below) is described by the narrator as ‘a fine gesso table, formerly at Stowe’, is certainly No.121 in the Exhibition catalogue; it is illustrated and described as ‘A George II gilt side table…formerly at Stowe’ and was offered for sale by the antique dealer and interior decorator Gregory & Co., then trading at 27 Bruton Street, London. The table was originally sold at the auction sale of the contents of Stowe House in 1848, following the bankruptcy of the Duke of Buckingham.

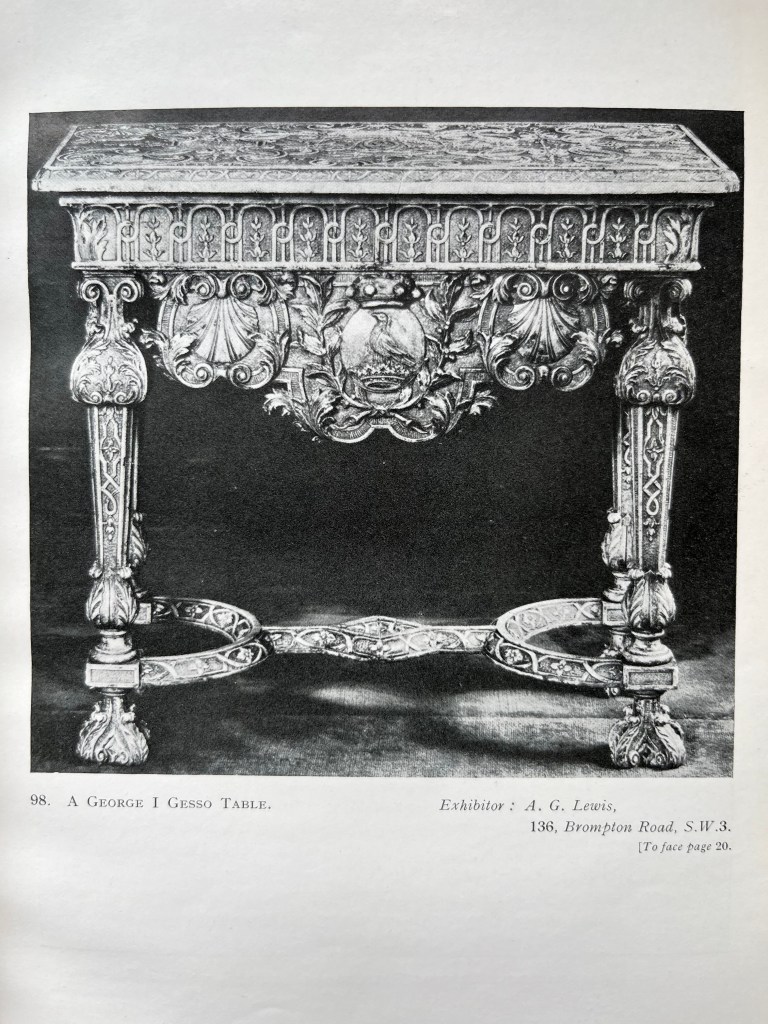

It has not been possible to trace the whereabouts of the side table, but interestingly, another giltwood side table from Stowe was on display at the 1932 Exhibition; No.98, ‘A George I gilt gesso table, circa 1715’, and offered for sale by the antique dealer A.G. Lewis, Brompton Road, London. This table (see below) is one of a pair (possibly three?) side tables associated with Stowe. In 1930, one table, (perhaps the same one in the 1932 exhibition?) was in the stock of the antique dealer Kent Galleries, Conduit Street (Kent Gallery are associated with The Spanish Gallery who offered the ‘Gothic tapestry’ at the 1932 Exhibition). One of the tables (perhaps the same one?) is now in the V&A Museum (see below too). The V&A table was sold to the V&A by the antique dealer Phillips of Hitchin in 1947, having been through the hands of a number of other antique dealers, including John Bly of Tring and Edinborough of Stamford. All of this highlights the significance of inter-dealer trading that sustained the antique trade for much of the 20th century.

9th object – (see below) the narrator describes a ‘spinning wheel, perfectly usable today’ as the next object. It is a ‘Sheraton spinning wheel, circa 1790….made by John Planta, Fulneck’; it was No.231 in the catalogue and was illustrated and offered for sale by the antique dealer Law, Foulsham & Cole, South Molton Street, London. There are several such spinning wheels by Planta, who was based in Leeds in the late 18th century – one example (although not the one in the 1932 Exhibition), remains in the collections at Temple Newsam, near Leeds.

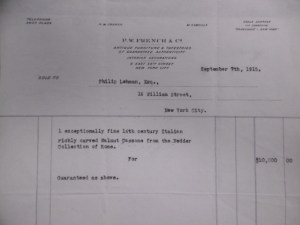

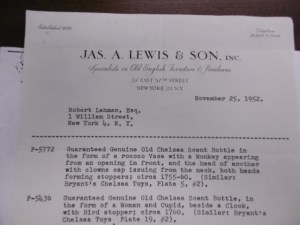

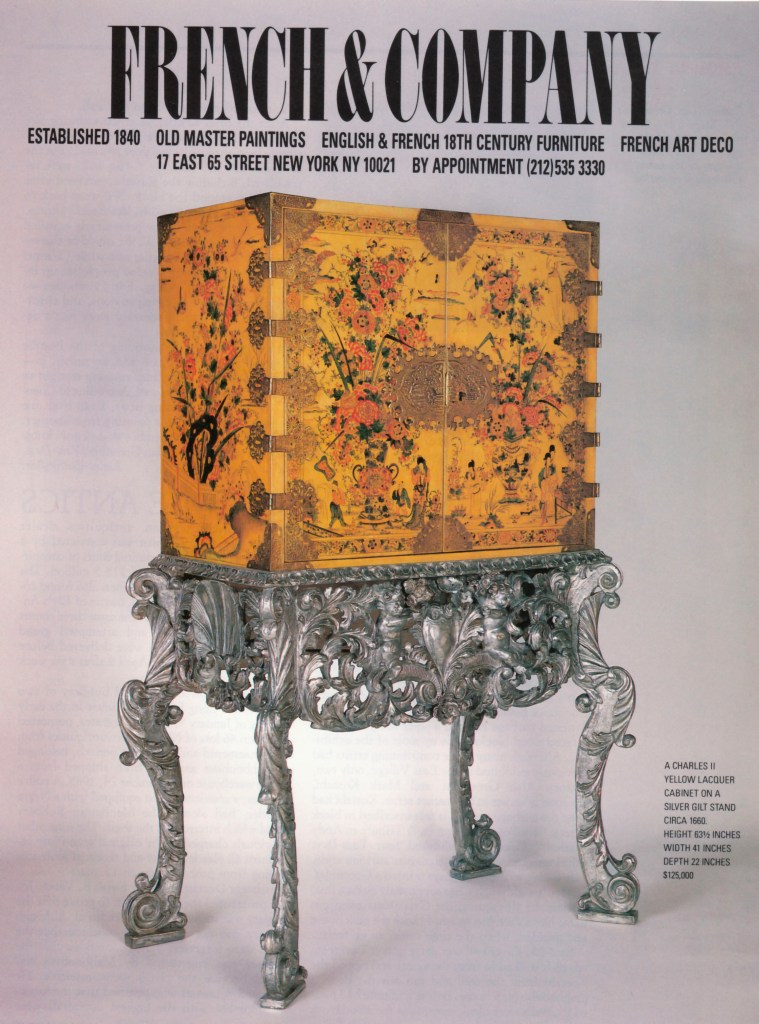

10th object – (see below) the narrator describes as a ‘rare cream lacquer cabinet, made towards the end of the 17th century’. This was No.31 in the catalogue, ‘a Charles II lacquer cabinet, circa 1680’ and was offered for sale by the dealer E.H. Benjamin, 39 Brook Street, London. White lacquer cabinets are the rarest of lacquer furniture, but even so it has not been possible to trace the cabinet – perhaps it has been lost? (Chris tells us that the cabinet on stand was in stock with the American antique dealers’ French & Co in 1987 (see below), so perhaps the cabinet is still in the USA?)

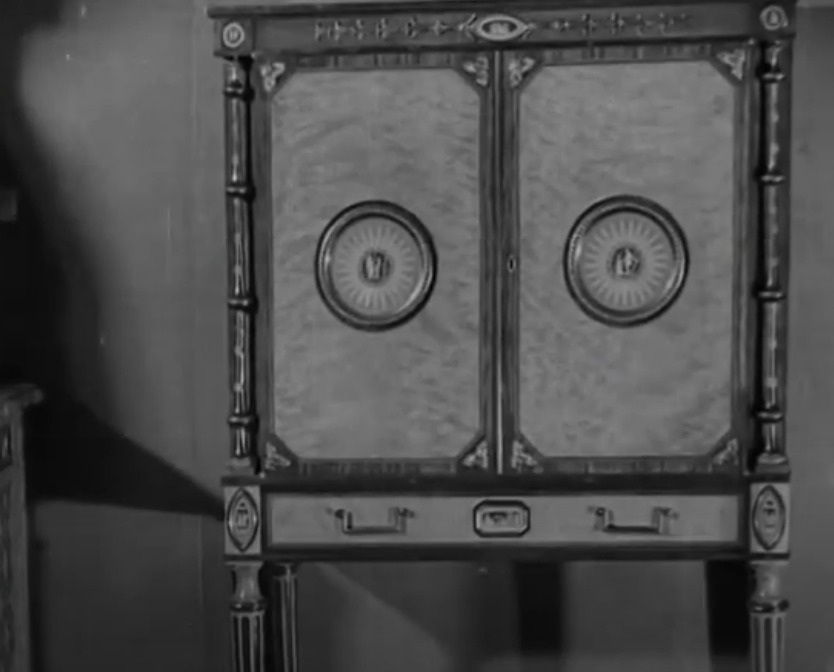

11th object – (see below) the narrator describes another cabinet, this time ‘a fine Adam satinwood example’ – he mentions that ‘it was purchased by the Queen at her recent visit to the exhibition’ (this would be Queen Mary, a very well-known collector of antiques). The cabinet is No.205 in the catalogue, described as ‘an Adam satinwood cabinet, circa 1780’, but is not illustrated; it was offered for sale by the antique dealer Mallet & Sons, one of Queen Mary’s favourite antique dealers. I can’t find the cabinet in Royal Collections, so perhaps the cabinet was sold from the collections or given away or was destroyed?

12th object – (see below) the narrator describes ‘a lovely satinwood side table’, ‘one of Lord Nelson’s gifts to Lady Hamilton’. This is one of 3 tables on display at the exhibition, No.241, ‘a set of three satinwood tables, circa 1795’; they were illustrated and were offered for sale by the dealer A.G. Lewis. Like the film, the catalogue mentions that the tables were presented by Lord Nelson to Lady Hamilton. Given the provenance, it’s surprising I can’t find them anywhere? Two of the tables were in the collection of Arthur Sanderson (1846-1915), the well-known collector in Edinburgh; they are listed in the auction sale catalogue of Sanderson’s collection sold by Knight, Frank & Rutley, Hanover Square, London, June 14th-16th 1911 as Lot 540 ‘A PAIR OF SHERATON SHAPED FRONT SIDE-TABLES, which (together with Lot 541 A SHERATON BOOKCASE) were ‘said to have been made by Sheraton for Lord Nelson and given by him to Lady Hamilton at Naples’; (our friend Chris Coles tells me that the Nelson tables were in the collection of the antique dealer George Stoner (of Stoner & Evans) in 1912; and that one of the tables was in the stock of Moss Harris & Sons in 1935; Chris rightly suggests that as the three tables don’t exactly match, they are more likely to have been separated – thanks again Chris!)

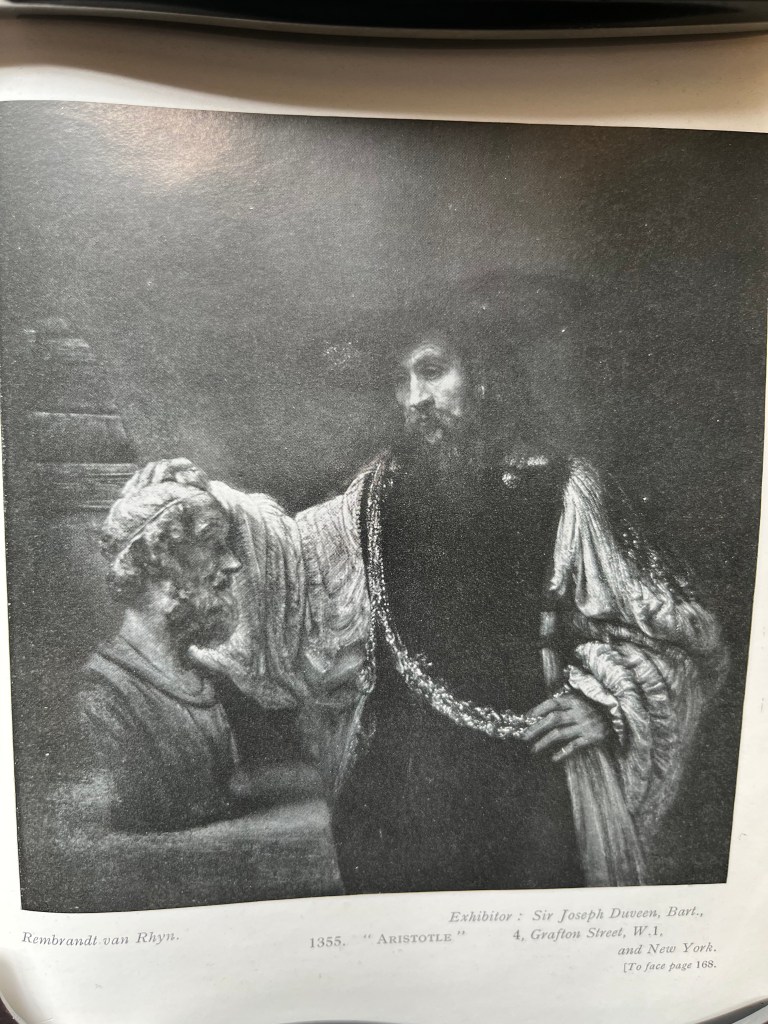

Finally, 13th object – the narrator highlights that this object (a painting by Rembrandt) is ‘the most valuable object here’. It is No.1355 in the exhibition catalogue, ‘Rembrandt van Rhyn (1606-1669), ‘Aristotle’, signed and dated 1653′. It was offered for sale by the world-famous art dealer Joseph Duveen (1869-1939). Duveen bought and sold the painting several times in the decades before the 1932 exhibition. He sold it to the art collector Alfred W. Erickson (1876-1934) in 1928 for $700,000, before buying it back and selling it to Erickson again in the mid 1930s for $590,000. It is now in the collections at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, where it has been since 1961.

The film of the Art Treasures Exhibition 1932, together with the catalogue of the exhibition, gives a fascinating insight into the publicity for one of the major commercial art exhibitions of the period and is a further demonstration of the significance of the antique trade in the circulation and consumption of antiques (and paintings) and their role in the development of public museum collections – and thanks again to Diana for sending on the link to the film!

Mark