We are delighted to present another of our occasional series of guest blog posts on the history of antique dealing in Britain – and welcome Andy King as author of this wonderfully detailed post on the Lock family of antique dealers; Thank you Andy!

Andy King I never knew my grandfather, Stanley Harry Lock, as he died before I was born – but knew that he was an antique dealer. I have been researching my family tree for over 25 years and have discovered that it was not just him and his brothers who were in the antiques trade, but his father, grandfather and uncles were too, operating over a dozen antique shops over the course of over seventy years. Thank you to Mark for allowing me to share some of their stories and add to research on the history of the antique trade.

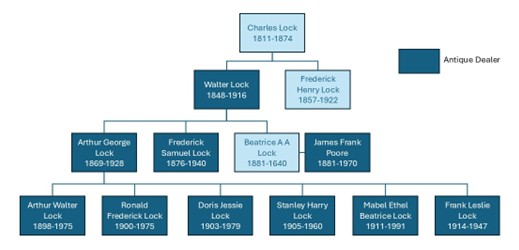

The first of my Lock family with connections to the antique trade was Charles, born c1811 in Taunton, Somerset. He was a Cabinet Maker. I don’t know how he got into this trade as his parents were farmers and his siblings’ occupations varied from dairyman to hairdresser. He and his wife Matilda (daughter of a Waterloo veteran) had six children, including Walter (born 1848) and Frederick (born 1857). By the 1881 census Walter and Frederick were in London, both upholsterers, living together at 9 The Mall, Kensington with Walter’s wife Jessie, their five children, Frederick’s recently married wife, two of Jessie’s brother’s (also upholsterers), a boarder who was a cabinet maker, also from Taunton, and a governess, quite a household.

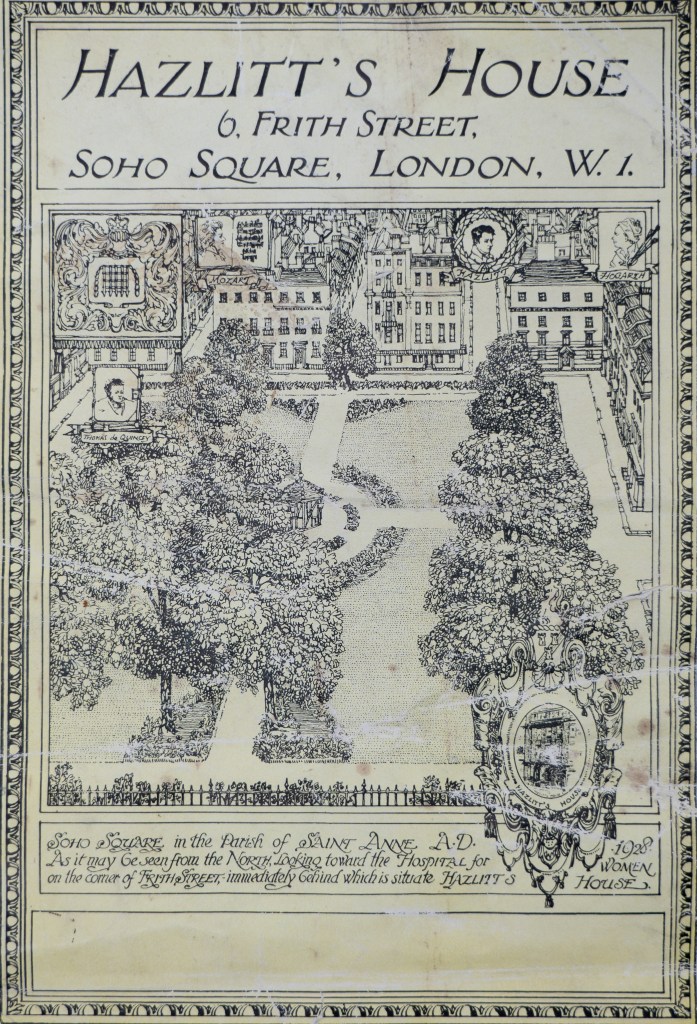

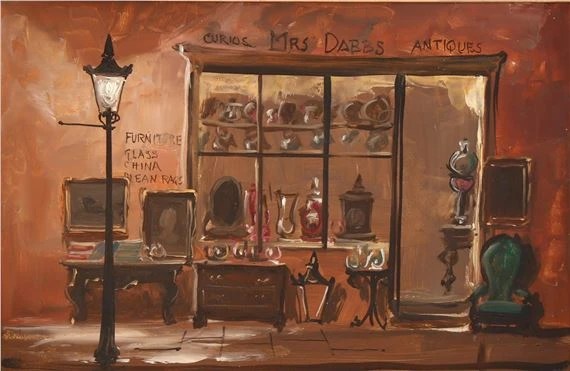

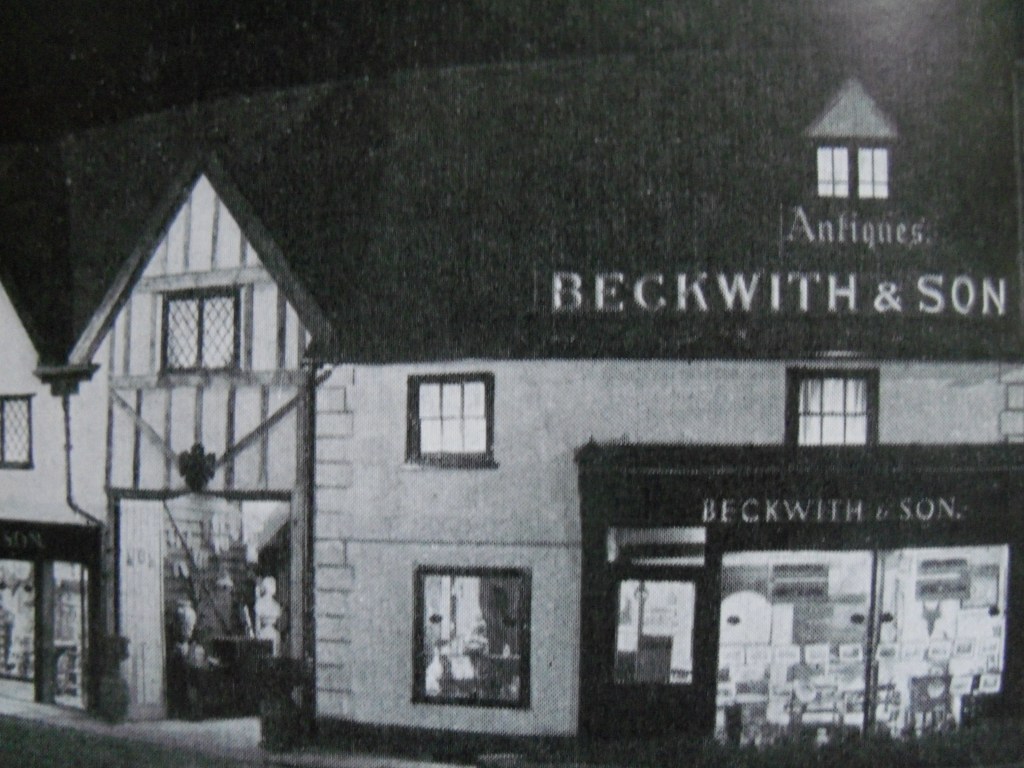

The first mention of them in business is the 1887 Post Office Directory where there is an entry for “Lock, Wltr. & Fredk., Upholsterers, 17 Devonshire Terr, Notting Hill Gate, E” (later renamed as 34 Pembridge Road). The family changed premises and business names a few times in the 1880s and 90s – A second entry appears in 1888 for “Lock, W & F, Upholsterers” at 12, The Mall, Kensington as well as one for Devonshire Terrace. By 1895 the shop at 12 The Mall was in Walter’s own name, and the following year later the listing is “Lock, Walter and Son, Upholsterers, 12 The Mall & 44 High St”. 1899 sees the first mention of a change in the nature of the business, which now shows as “Lock, Walter and Son, Antique Furniture Dealers, 29 & 44 High Street, NH”.

Walter and Jessie had five children, three boys and two girls: Arthur George, Ernest, Frederick Samuel, Mabel and Beatrice. Arthur and Frederick followed their father into the antiques trade, and Beatrice married into it.

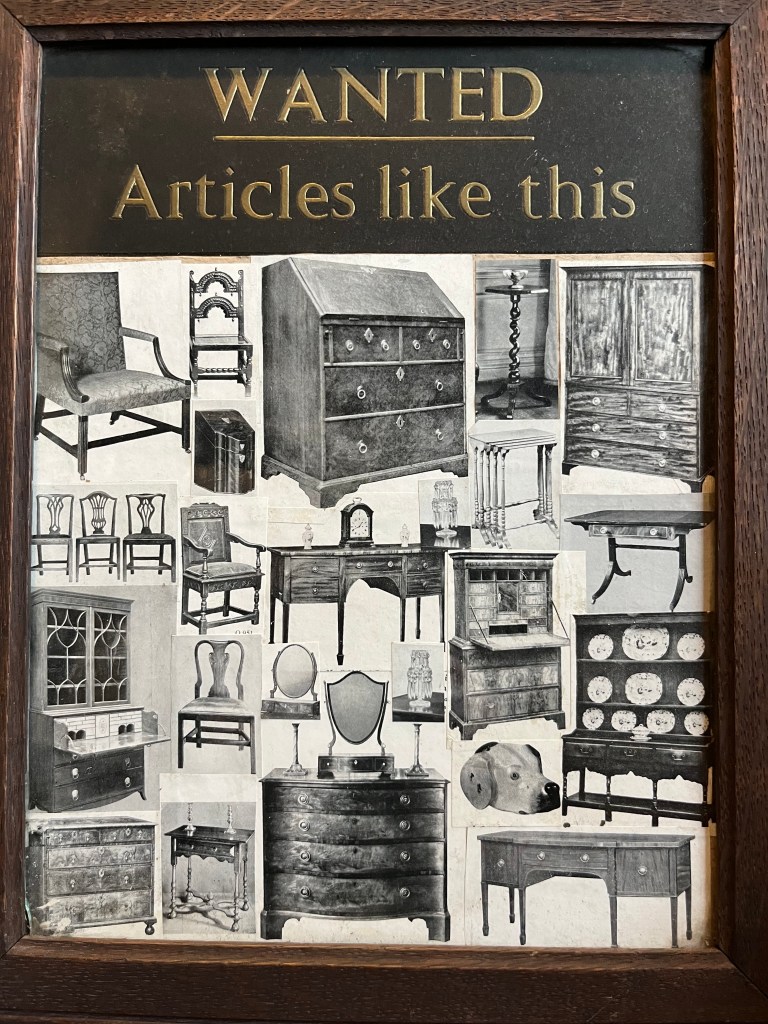

The family clearly maintained links with Taunton, and with antique dealers there, as an 1899 newspaper article tells how the Locks were sued by Esau Winter of Winter & Son, furniture and antique dealers of Bridge Street and Station Road, Taunton to recover £23 (around £2,500 today) for a set of 12 “Gothic Chippendale” chairs which the Locks had bought but then returned as they were allegedly not to be what they were claimed to be. The case went against the Locks, and the judge told them that they should “have sold the goods and then sued for the balance in damages for breach of implied warranty” – I wonder if they ever had cause to use that advice?

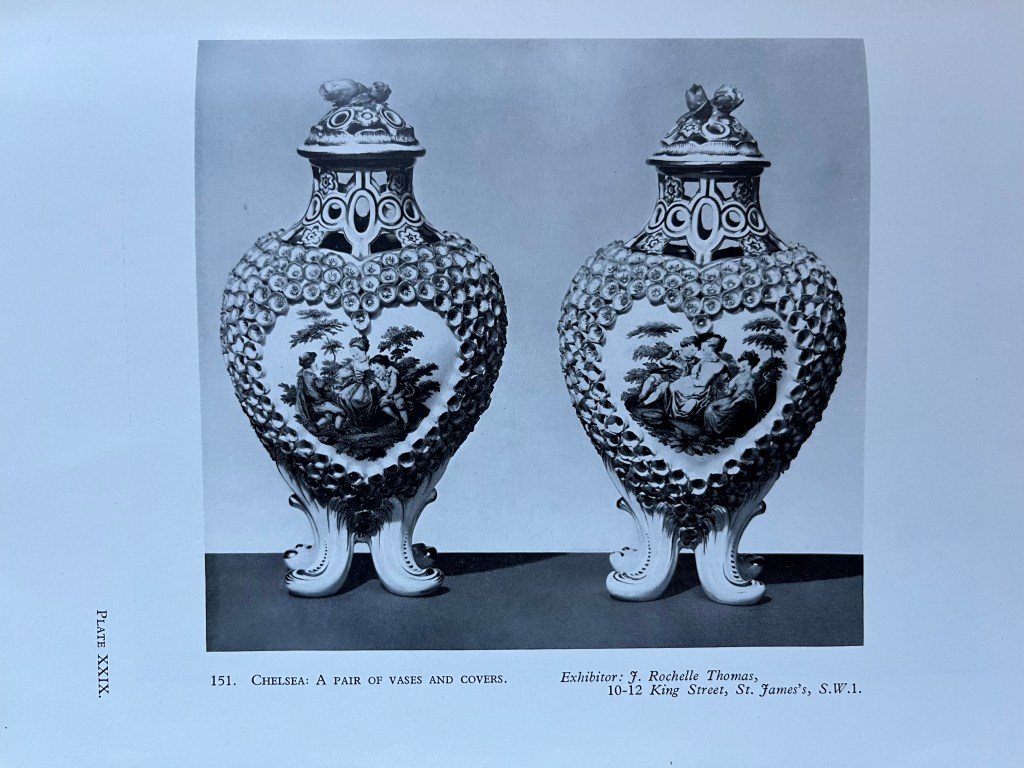

They faced a second court case only four years later – this time it was they who were selling things were not what they claimed to be. They were summonsed by the Worcester Royal Porcelain Company Limited charged with “infringing the Merchandise Marks Act by exposing for sale, as old Worcester ware, two vases to which the Worcester trade mark had been falsely applied”. The vases were marked up at £65, but if genuine would have been “worth a thousand guineas”. The vases had apparently been “taken by one of the sons from a customer in exchange for a couple of Louis XIV cabinets”. I wonder whether they thought he had made a good deal on the exchange, or whether they did not know the genuine value of the vases. They were given a penalty of £5 plus three guineas costs.

Despite the court cases the family were clearly making a good living from the business as they moved into two large properties in Campden Hill Road – one occupied by Arthur George and his family, with Frederick Samuel and his wife next door. My grandfather was born here in 1905. The applications for the houses to be connected to mains drainage under the Metropolis Management Act were submitted under the name of “W. Lock & Sons” in September 1903. In 1911 there were three shops listed: “Lock, Walter and Sons, Dealers in Antiques: 44 High St, Notting Hill Gate: & 37 Queens Road, Bayswater: & 147 Brompton Road, SW”.

The London Gazette of 16th January 1914 reports that the partnership between Walter Lock, Arthur George Lock, and Frederick Samuel Lock, trading as Walter Lock and Sons was dissolved by mutual consent on Christmas Day 1913. I wonder what triggered the decision? Interestingly, Walter’s will, dated 21st April 1914, shortly after the marriage to his second wife Sophia (the widow of his first wife Jessie’s brother Henry) explicitly names the “four” children by his first wife, omitting Arthur George. A codicil dated June the following year states that “in the event of any beneficiary…raising any question or dispute…then his or her interest…shall immediately and entirely cease”! Clearly, Arthur George was not in Walter’s good books.

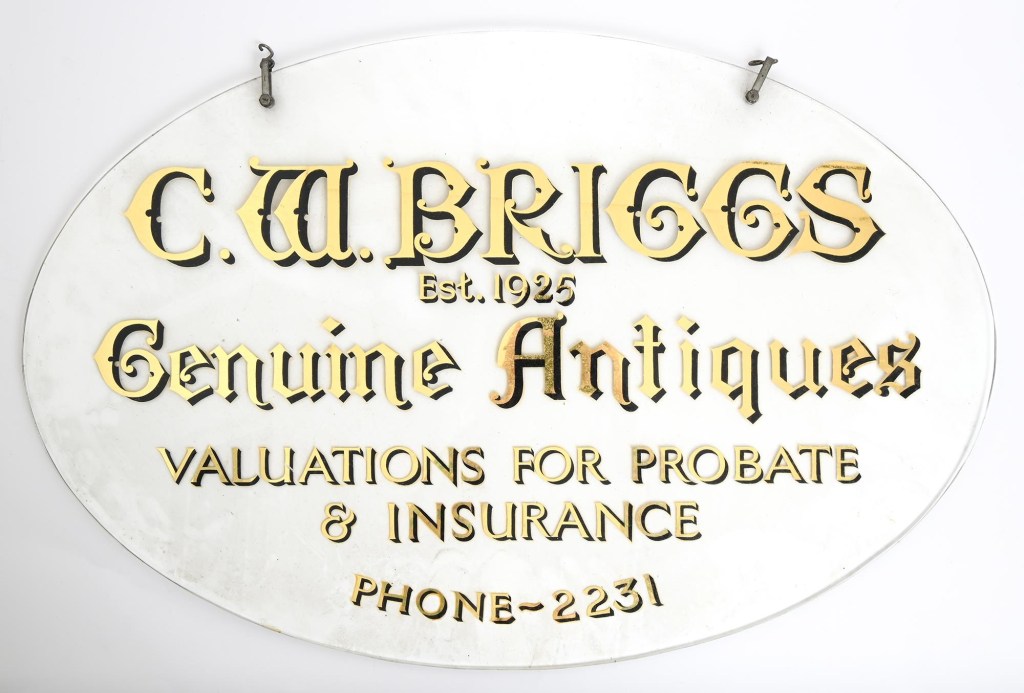

In 1915, 44 High Street is now listed as “James F. Poore, Antique Furniture Dealer”. James, or Frank as he was more commonly known in the family, had married Beatrice Alice Augusta Lock, daughter of Walter, in 1909. He too had started out as an upholsterer before becoming a furniture salesman for a London store. Frank Poore moved to premises at 5 Wellington Terrace, Bayswater. An article in The Kensington News and West London Times from 14th May 1965 gives a portrait of him still in business there at the age of 84 saying “I’ll not retire yet!”. He died in 1970 leaving no children.

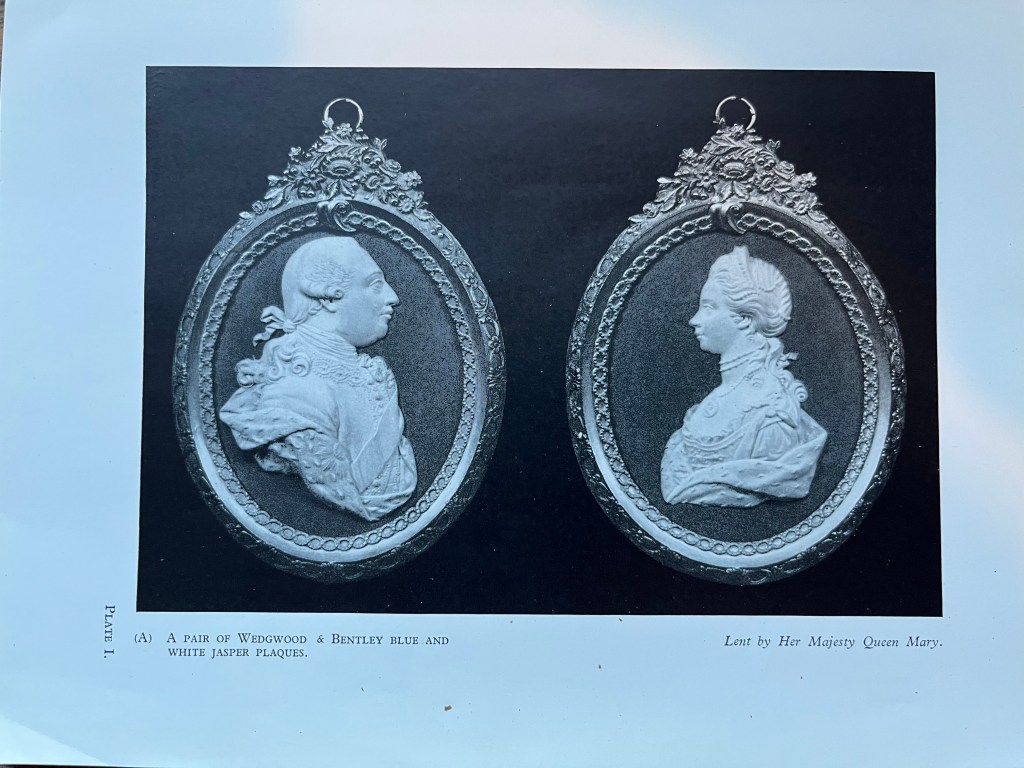

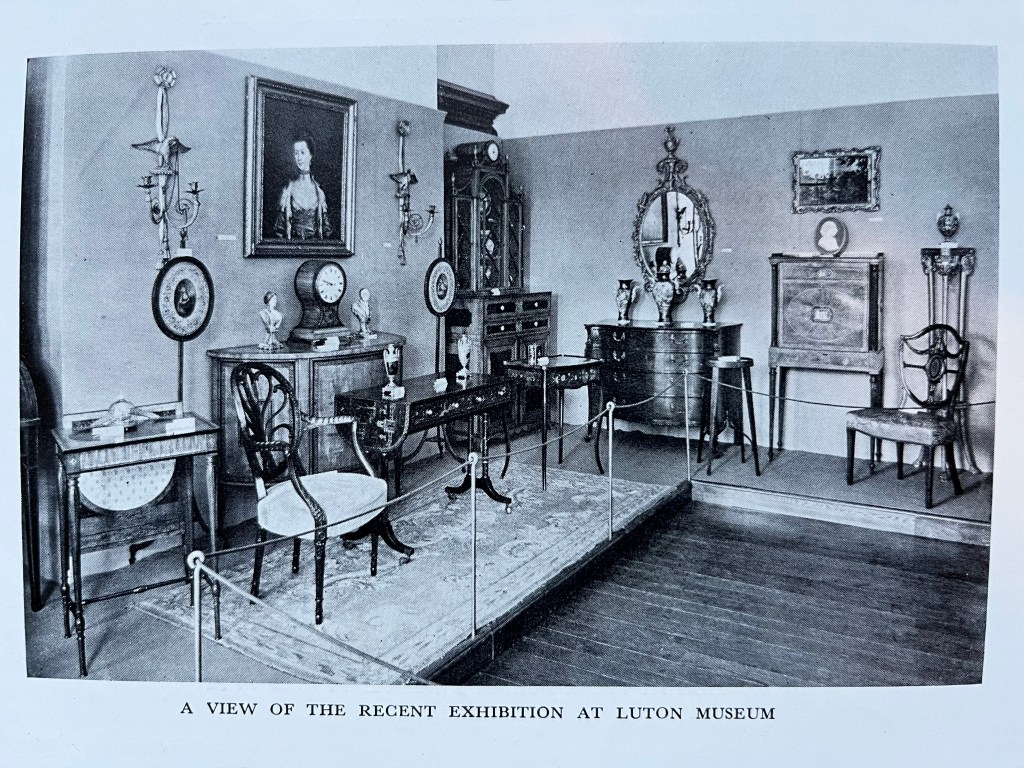

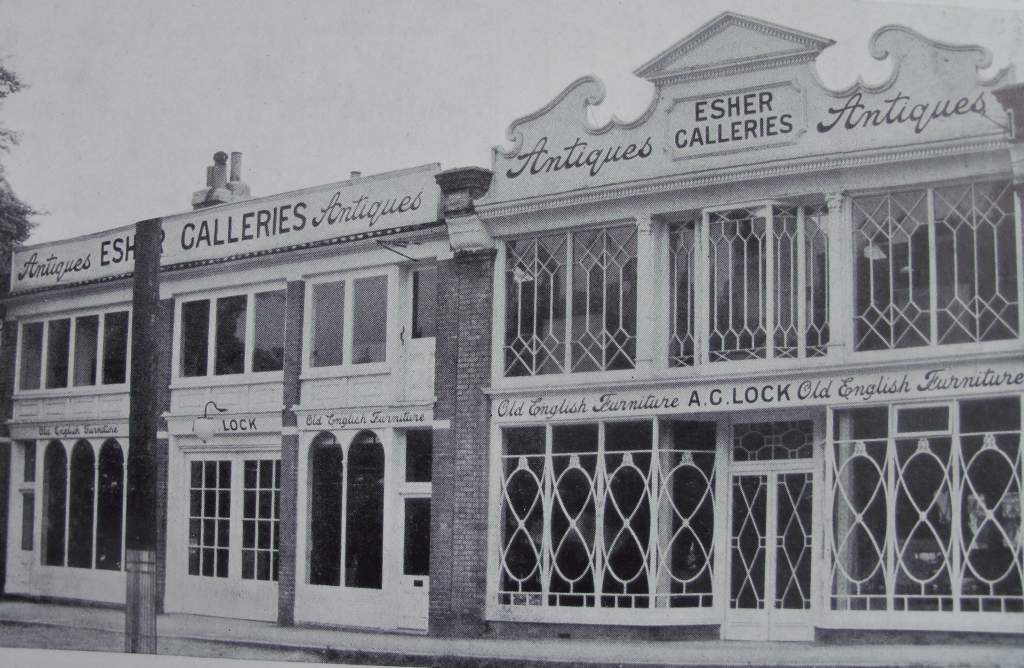

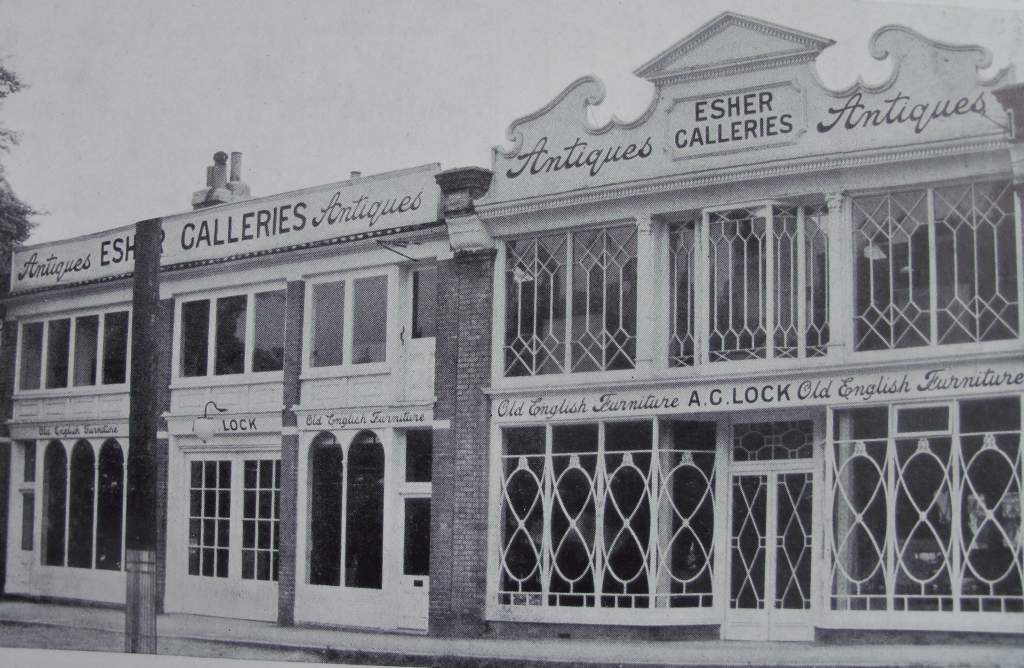

Also in 1915 Arthur George was listed at 112 Victoria St., SW1 – where he remained until 1927 when the end of the lease saw him move to new premises at Esher Galleries, High Street Esher. He regularly advertised in collectors magazines such as The Connoisseur, Country Life, and Apollo, and was an exhibitor at the annual Grosvenor House Antiques Fair.

Arthur George had married Harriet Illsley in 1897. Harriet was the daughter of a bricklayer from Brixton. I have often wondered how they met as their worlds were so far apart, both physically and socially. They had six children, four boys and two girls, all of whom were in the antiques trade, albeit some rather briefly. In the 1921 census, Arthur George was listed as an employer at 112 Victoria Street, SW1, and the eldest three children Arthur, Ron and Doris were employed as assistants.

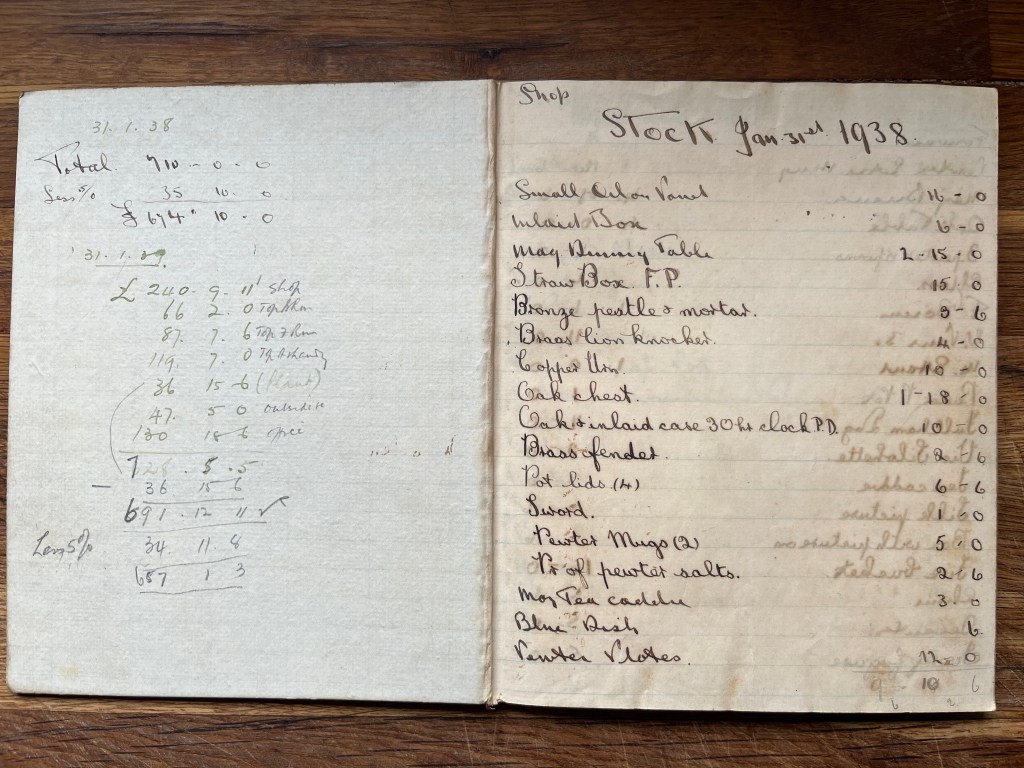

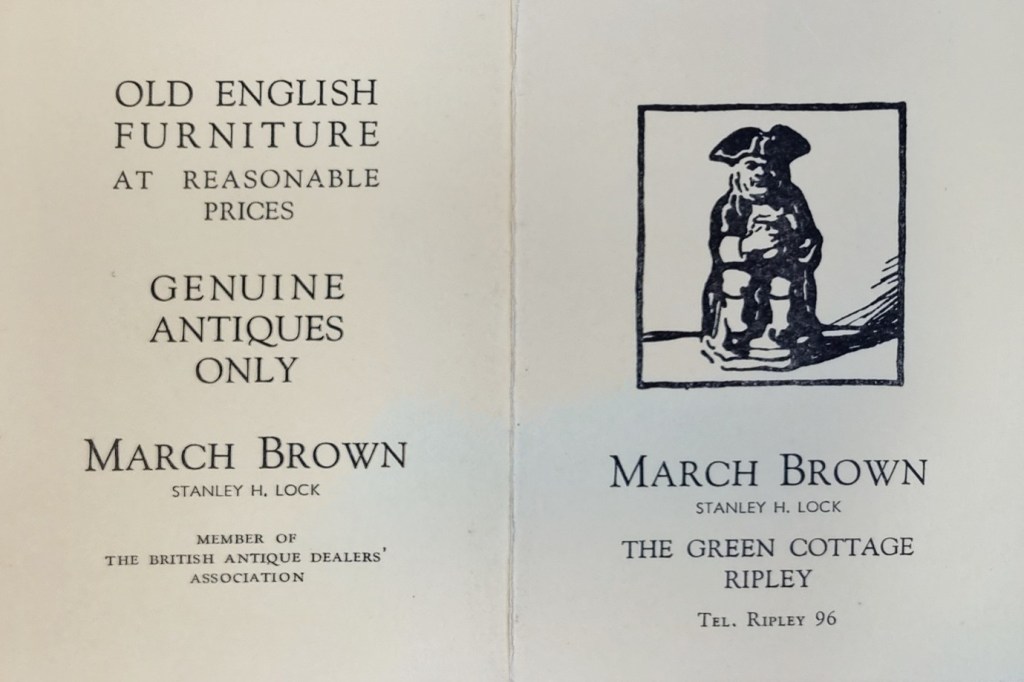

Arthur and Ron, the eldest two children opened their own shop at 88-91 Petty France in 1922. Sadly, Arthur George died soon after opening the shop in Esher, and the remaining four children ran it in partnership until 1937 when Doris and Mabel left, and then a year later Frank too left the business, leaving just Stanley, who also bought a second business, “March Brown” of Green Cottage, Ripley, Surrey in December 1937, and continued under the same name.

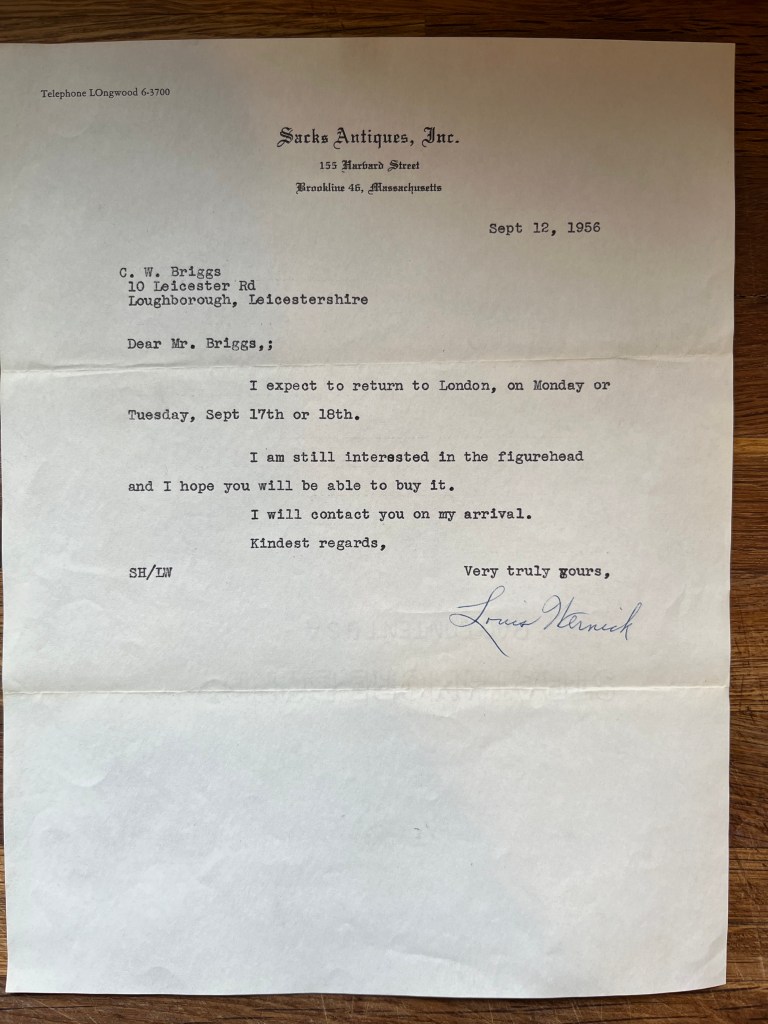

Frank served in the Royal Engineers during WWII but was discharged in 1944 on health grounds. He ran the Weybridge Furniture Mart, but sadly died in 1947 at the age of 33. Stanley ran both businesses until early in the war, when he left the antiques trade and went to work for the Board of Trade War Damage Commission as a valuer where he remained until his death at the early age of 55 in April 1960. When Stanley left the trade the shop at 91 High Street, Esher became H.E. Marsh, Antique Dealer. Arthur took over Esher Galleries and the business continued trading as A.G. Lock. He also had a furniture repair workshop linked to the shop. A 1950-51 antiques year book has two entries under Provincial Dealers in Esher, one for H.E. Marsh at 91 High Street, and one for A.G. Lock Esher Galleries.

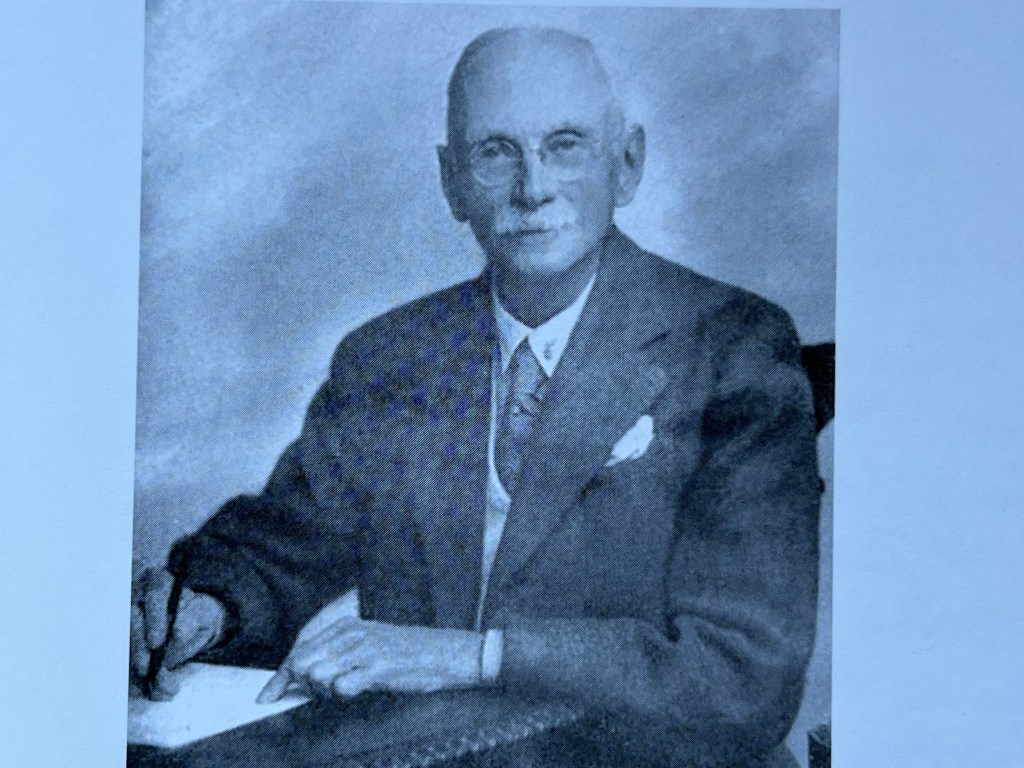

Arthur and Ronald were in business together in Petty France until 1930 when Arthur moved to Vine House, Cobham, where he remained until retirement in the 1960s. Ron continued in Petty France until 1936 before moving to 152 Brompton Road. Ron regularly exhibited at the annual Antique Dealers’ Fair at Grosvenor House and was on the fair’s advisory council on furniture. He advertised in magazines such as Apollo, The Connoisseur and Country Life, and by the 1950s the advertisements show that he was specialising in bookcases. Ron was also president of the British Antique Dealers Association (BADA) in 1952-3. Ron sold up and retired to Florida in the mid 1960s. Arthur and Ron both died in 1975 leaving no children, and the Lock involvement in the antiques business came to an end.

However, the Lock business names continue to turn up even now, last year a set of chairs were sold at auction by Dreweatts of Newbury, the description reading “A SET OF TEN GEORGE III MAHOGANY DINING CHAIRS THIRD QUARTER 18TH CENTURY AND LATER ADAPTED Comprising two arms chairs, the arms a later addition and eight chairs with drop-in seats, each with plaque to seat rail for ‘A. G. LOCK, OLD ENGLISH FURNITURE, ESHER, SURREY’

Andy King.